Seventy years ago, Harry Markowitz gave us the recipe for the optimal portfolio: combine assets to maximize expected return for a given level of risk. In theory, it’s beautiful. In practice, it has been nearly impossible to implement.

Why? Because the ingredients—expected returns and the covariance matrix of individual stocks—are not observable and are notoriously hard to estimate. Even small errors in estimation lead to extreme, unstable portfolio weights and poor out-of-sample performance. That’s why, despite decades of research, the practical Markowitz portfolio often underperforms something as naive as the 1/N strategy.

So the puzzle is: how can we actually build a portfolio that comes close to the theoretical optimal one?

The idea: Basis Portfolios

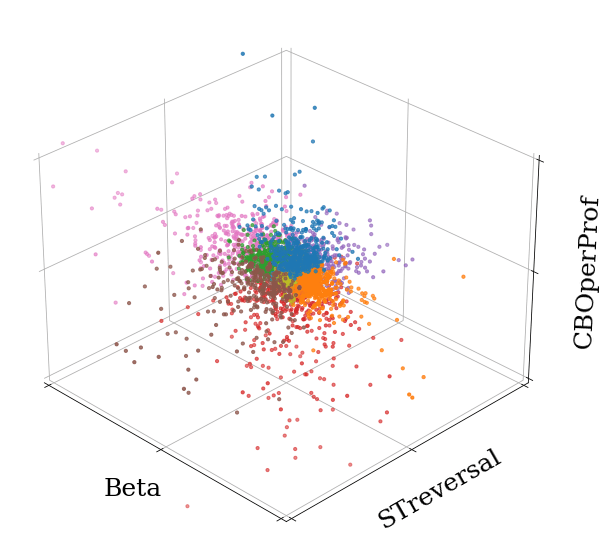

The solution I propose is to work with a small set of “basis portfolios.” These are portfolios that satisfy two properties:

- Within each basis portfolio, stocks are as similar as possible in their fundamentals.

- Across portfolios, stocks are as distinct as possible in their fundamentals.

Think of it as clustering stocks by characteristics. If two firms look alike on dozens of financial and price-based metrics, they belong in the same group. If they look very different, they should be in different groups.

By doing this, each basis portfolio is well-diversified, while the set of basis portfolios spans the full range of differences in fundamentals.

Why should this work?

If both expected returns and covariances are functions of firm characteristics (as suggested by a growing literature), then:

- Stocks that are similar in characteristics will have similar risks and returns.

- Portfolios that are maximally distinct in characteristics will also be maximally distinct in mean-variance space.

This means basis portfolios are the right “building blocks” for the optimal portfolio.

In fact, my approach can be seen as a high-dimensional generalization of the familiar portfolio sort:

- If there were just one variable (say, book-to-market), sorting on it gives the standard deciles.

- With hundreds of characteristics, we need a high-dimensional sort that takes them all into account at once.

Results: A better optimal portfolio

Empirically, the optimal portfolio spanned by these high-dimensional basis portfolios performs impressively:

- Monthly alpha ~1.7% (t = 11.1).

- Annualized Sharpe ratio ~1.8.

- No extreme weights on any individual stock.

This outperforms:

- Traditional characteristic sorts (size, value, momentum, etc.).

- Correlation-based or industry portfolios.

- And of course, it handily beats 1/N.

In other words, by carefully constructing the building blocks, the Markowitz portfolio actually delivers.

A new perspective on portfolio construction

The key insight is this:

- Traditional sorts on one or two variables (like size and value) ignore the zoo of other characteristics, so the resulting portfolios still comove heavily. That leads to ill-conditioned covariance matrices and fragile optimal weights.

- My high-dimensional sort produces portfolios that are well-diversified within, far apart across, and thus robust in mean-variance space.

The result is an optimal portfolio that is both stable and high-performing.

The basis

By rethinking the building blocks—not assets, not single-characteristic sorts, but basis portfolios built on high-dimensional fundamentals—we can make the optimal portfolio a practical reality.

That, in short, is the basis of Basis Portfolios.

Leave a comment